This column was originally published in the September 2025 issue of ITE Journal.

The great critique of planning is that it’s not rooted in reality — it’s too aspirational, too visionary, and lacks meat on the bones. The perception usually originates from the not-inconsequential gap between planning and engineering. This is especially true with comprehensive planning, where a citywide vision must be established and recommendations provided for the community as a whole.

Comprehensive plans eventually result in real projects, many of which are transportation projects, but the hand-off from planning to engineering can be tricky. How can planners do a better job of passing the baton, and how can engineers start to reach for it?

In some communities, a different approach is emerging. Planners are pulling one layer of a comprehensive plan into the next step of the planning-to-engineering life cycle. Typically used as an effort to create efficiencies or cost-savings, this approach is also bridging the gap between planning and engineering. This makes for quicker implementation and ultimately, stronger communities.

This article will describe this approach and highlight a project in Bellevue, Nebraska that expedites the planning-to-engineering life cycle.

A Mile Wide and an Inch Deep

Comprehensive plans are the leading edge of planning projects. They are often the first step in the planning-to-engineering life cycle; they set the vision for the future of a city, and they can be a lot of fun.

Comprehensive plans are only the first step.

Conducted by municipalities every five to 20 years, these long-range citywide plans try to achieve a lot. They must provide recommendations for many layers, including land use, development, economic health, transportation, placemaking, parks and recreation, environmental resiliency, quality of life, and more. Comprehensive plans are aptly named.

Each of these layers is explored through data analysis and community engagement. Spatial and policy-related strategies are then provided for each layer in the form of one unified plan document. Many modern comprehensive plans number 300 pages, providing maps, graphics, and text that articulate a community’s vision. But with so much to cover, how do these plans result in real projects that can be designed and constructed tomorrow?

Great comprehensive plans document the why, the what, and the how. The future vision is the why, capturing the values and aspirations of the community. The plan’s recommendations are what a community wants to achieve (e.g., safer streets, a more robust downtown economy, denser development). But providing the how is what transforms a document into a tool that results in real projects.

The how is often depicted in implementation tables that identify policy solutions, partnerships, initiatives, and projects. Things like zoning amendments, creation of a public arts commission, and intersection safety improvements are among hundreds of possibilities.

Comprehensive plans should pinpoint not only the greatest needs, but specific steps to achieve community goals. Performing this citywide evaluation helps set priorities and get future plans and projects programmed and funded. But even the best comprehensive plans only go so far.

Feeling like this still leaves a bit to be desired? That’s because it does. Comprehensive plans are intended to create building blocks for subsequent system plans and areas plans that ultimately lead to final design.

The Next Step in the Life Cycle

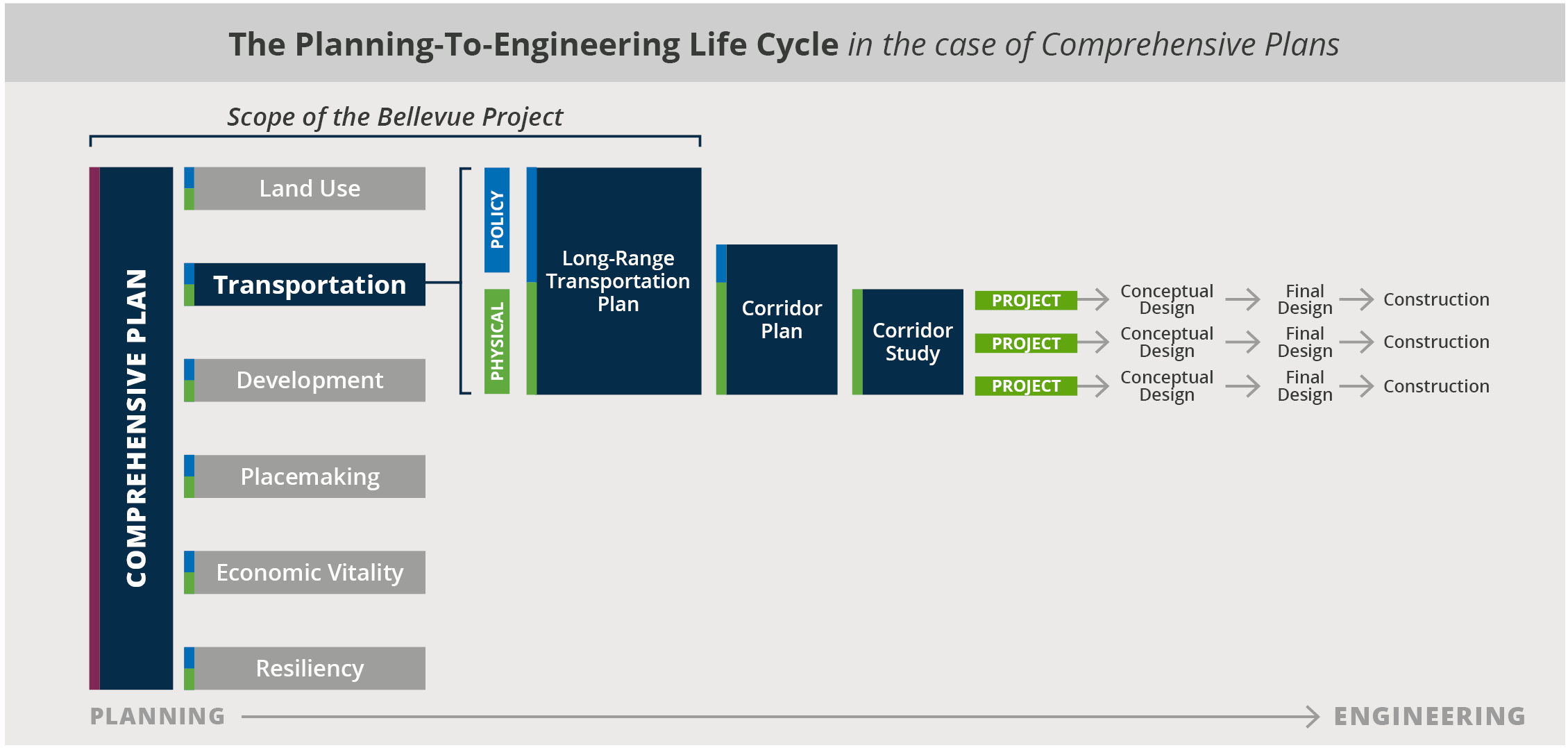

An important order of operations creates continuity between the community’s overall vision and implementation of projects. The cycle often follows a series of steps, as follows:

1. Visioning and citywide planning (accomplished through a comprehensive plan)

2. System planning (a transportation plan or parks system plan) or area planning (a downtown plan or corridor plan)

3. Conceptual design

4. Final design

5. Construction

Let’s assume a community has a great comprehensive plan it actively uses to make decisions. The city would then develop a transportation master plan, followed by a specific corridor plan, before a series of engineering and design projects finally make their way to construction. Comprehensive plans are only the first step.

Advancing the Transportation Layer

Each layer of a comprehensive plan should be evaluated in its own right. Let’s use transportation as an example.

While recommendations are provided in the comprehensive plan for the citywide transportation network, it is just one layer of the plan. The wide scope of the comprehensive plan does not allow for a deep dive into the transportation system. Instead, the transportation layer must evaluate multiple modes of transportation and how they interact with things like land use, development, and community character.

The onus is on planners, engineers, city leadership, and elected officials to create continuity in the life cycle.

The comprehensive plan must also identify large-scale system enhancements including physical and policy changes. After completing the comprehensive plan, the next step is the creation of a transportation plan.

But things can get lost between planning and engineering. Years pass, cities grow and develop, elected officials turn over, and engineers advance the ball without consideration of the planning work that captures the larger picture for a community.

And who can blame them? Engineers must fix an intersection that everyone knows is unsafe. This task is among dozens of competing priorities and there isn’t time to read a 300-page plan to figure out why. If the planners did not intentionally include engineers in the plan development, engineers are (for good reason) even less inclined to consult the document.

This pattern continues and projects may begin to misalign with the city’s vision. This represents one symptom of the chasm that can exist between planning and engineering. The onus is on planners, engineers, city leadership, and elected officials to create continuity in the life cycle.

What can be done to lessen the gap?

In the Case of Bellevue

The City of Bellevue, Nebraska, recently took a new approach that has resulted in a stronger tie between comprehensive planning and its implementation for transportation. Bellevue partnered with a project team of planning and engagement specialists to conduct a joint comprehensive plan and long-range transportation plan.

This parallel planning effort took place at a pivotal point in the city’s growth and development, as the city was seeking a cohesive community vision and guidebook for the future.

"It’s very helpful to have one document with specific, achievable goals.”

“When we decided it was time to update the comprehensive plan, it made sense to include the transportation plan as well,” said Tammi Palm, Bellevue’s planning director.

“We knew both plans were crucial to our future growth and development. Combining the plans was a natural fit, and it streamlined our process. It made sense to have community conversations around future land use and transportation planning together. Moving forward, it’s very helpful to have one document with specific, achievable goals.”

This project advanced the transportation layer to the next step of the life cycle in tandem with the comprehensive plan. This approach created efficiencies in the planning process, better aligned recommendations, and further bridged the gap between planning and engineering.

The two plans were developed as one during a year-long planning process. At each phase, the comprehensive plan was developed in layers while the transportation layer was taken to the next level of analysis and depth. This project’s place in the planning-to-engineering life cycle is modeled in Figure 1 (see second photo).

The process for comprehensive plans is similar to that of a transportation plan. As such, the city approached the project in parallel phases for existing conditions, visioning, community engagement, plan development, and implementation.

While the comprehensive plan prioritized holistic community visioning, the transportation plan dug deep into the issues facing Bellevue’s mobility and connectivity.

That depth was reflected in each phase of the process. The project team considered existing conditions, and the community was evaluated as a whole, with extra time and resources dedicated to understanding the transportation system.

Similarly, the comprehensive planning process executed a citywide visioning exercise, and a transportation-specific vision was also developed. This sub-step to the comprehensive plan took place during the same community workshop.

As the team broached plan development, transportation planning took place concurrently and collaboratively with the creation of the comprehensive plan. While the comprehensive plan comes first in the life cycle, this exercise in joint planning allowed the two to build off each other far more than separate processes would allow.

The project team prioritized collaboration between planners and engineers to identify opportunities for the transportation plan to advance the goals of the comprehensive plan, and vice versa. The engineering perspective brought critical insights into the development of the plan.

After the project team developed recommendations for both plans (the what), the focus shifted to positioning for implementation (the how) to reinforce its value as a tool.

The last section of the joint plan is the “action plan,” providing 24 pages of detailed tables with physical projects, policy recommendations, partnership opportunities, and citywide initiatives.

"Combining the plans was a natural fit."

The transportation plan reflects the stark difference between comprehensive planning and the level of detail associated with the next phase of the planning-to-engineering life cycle.

The implementation section of the transportation plan includes specific corridor studies, signal timing projects, intersection improvements, updates to the city’s roadway classification system, and more. This reflects not only great planning, but the integration of the practical and project-focused perspective of the engineers on the project team.

From start to finish, the team focused on aligning the plans. The joint planning effort facilitated the development of a cohesive set of recommendations. This is not always the case when the transportation plan comes later, and without regard for the recommendations of the comprehensive plan.

The planning effort intentionally involved the Bellevue Public Works Department, city engineers, and consultant team engineers to enhance the quality of recommendations.

Integrating the engineering perspective into the planning effort created a more holistic and interdisciplinary approach that resulted in more practical outcomes and projects. This joint planning effort advanced the city into the next step of the life cycle and the city is now better positioned for implementation through engineering and design.

Originally an effort to create efficiencies, this highly visible and momentous project provides compelling evidence for a new approach to advancing the typical planning-to-engineering life cycle.

The Trend in Joint Planning Efforts

Joint planning efforts are becoming more common. Aside from the City of Bellevue, other communities are tackling planning projects in tandem.

The City of Princeton, Texas, is currently developing its comprehensive plan alongside its parks and trails master plan (another instance of system planning) and the City of Royse City, Texas, is approaching its comprehensive plan alongside its downtown plan (an instance of area planning). This trend can also be seen in other cities throughout the United States.

This multidisciplinary approach results in stronger recommendations and, ultimately, stronger communities.

Joint planning efforts are becoming a viable approach as cities look for opportunities to streamline the planning-to-engineering life cycle, create efficiencies and cost-savings, avoid engagement burnout, and enable immediate action on a community’s most dire needs.

This approach supports municipalities’ goals to expedite, align, and implement plans. These goals are furthered by the intentional integration of engineers into the planning process.

Integrating Planning and Engineering

Planners, wondering how to get the engineers to buy into your plans?

Get them involved. It’s so simple. When you drag or bribe your friendly neighborhood engineer to a community visioning workshop or charrette, they will start to get it. They too are in the business of enhancing communities and improving quality of life.

Bellevue was awarded for its "comprehensive plan that advances the science and art of planning.

The Bellevue project is a prime example of the type of multidisciplinary approach that results in stronger recommendations and, ultimately, stronger communities. The engineers may chuckle at your choice of tropical-colored sticky notes, but never at the value of the planning work.

And if you get them plugged in soon enough, civil engineers provide critical insights into the development of plans that are geared toward implementation.

They will dig deep when you shift your focus from the what to the how, and they will see new opportunities and constraints in a way that planners, at least many of us, are not trained to do. This is the stuff that gets everybody sprinting at the same pace and ready to pass the proverbial baton.

And engineers, it’s time to reach for the baton.

Planners want to see our plans implemented, and we are motivated to improve communities through physical projects and policy changes that lead to physical change. Yes, we like the squishy stuff—visioning exercises, community engagement, infographics, 3D visualization—but we also want to see the community’s vision realized.

We use these tools to capture the big picture and that informs the next phases of the life cycle, which are ripe for you to bring to life.

Read those comprehensive plans, dig into the work that’s been done to articulate the citywide vision, and reach out to planners to understand the complexities of land use, growth, development, and policy. These are the intricacies that should contextualize and inform design.

Plug into system planning and area planning and cultivate more continuity in the planning-to-engineering life cycle. Let’s work together to create stronger communities.

Pinpointing Success

Bellevue’s Comprehensive Plan + Long-Range Transportation Plan was unanimously adopted by the City Council in November 2024. The plan has already seen significant implementation and momentum, including the master planning and design of a new entertainment district and numerous transportation improvement projects. The joint plan is being used as a crucial decision-making tool and printed copies can be found throughout Bellevue City Hall.

The plan was also awarded the Daniel Burnham Award by the Nebraska Chapter of the American Planning Association in March 2025. This honor recognizes “planning excellence for a comprehensive plan that advances the science and art of planning.”

The success of Bellevue provides compelling evidence for the value of joint planning efforts that advance the planning-to-engineering life cycle, but also for the benefits of intentional integration of planning and engineering.

Both point to the importance of bridging that gap. Both support the advancement of our fields. And both spur the creation of stronger communities.

©2025 Institute of Transportation Engineers, www.ite.org.

Used with permission.

.avif)

.avif)